Introduction to Acceleration Sensors

Working principle of an acceleration sensor

📅 Last Updated: November 2025

Note: This article has been updated to reflect the latest developments in acceleration sensor technology, including MEMS advancements, AI integration, and emerging applications in IoT and autonomous systems.

📑 Table of Contents

II. Classification of Acceleration Sensors

6. Resistance/Impedance Considerations

IV. Applications of Acceleration Sensors

4. Electronic Compass Tilt Correction

10. Device Orientation Detection

V. Installation Considerations

VI. Future Trends (2025 and Beyond)

I. Working Principle

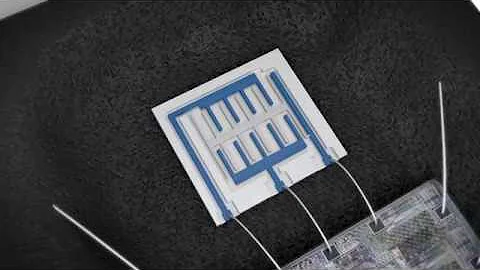

Figure 1. Acceleration Sensors

Acceleration sensors, also known as accelerometers, are devices that measure acceleration forces. These forces may be static (like gravity) or dynamic (caused by moving or vibrating the sensor). The fundamental principle of linear acceleration sensors is based on Newton's second law of motion:

A (acceleration) = F (inertial force) / M (mass)

By measuring the inertial force acting on a known mass, we can calculate the acceleration. Modern acceleration sensors typically use electromagnetic force to balance the inertial force, establishing a relationship between force and electrical current or voltage output.

Most acceleration sensors operate based on the piezoelectric effect. This phenomenon occurs when mechanical stress is applied to certain crystalline materials, causing them to generate an electrical charge. As defined: "When external force is applied to a heteropolar crystal without a symmetric center, the crystal not only deforms but also changes its polarization state, establishing an electric field within the crystal. This polarization phenomenon caused by mechanical force is called the direct piezoelectric effect."

Figure 2. Piezoelectric Effect

General acceleration sensors utilize the characteristic of crystal deformation caused by internal acceleration. This deformation generates a voltage proportional to the applied acceleration. By calibrating the relationship between voltage and acceleration, the sensor converts physical acceleration into an electrical signal.

While piezoelectric technology is common, other methods exist for creating acceleration sensors, including:

Piezoresistive technology - measures resistance changes under stress

Capacitive effect - detects capacitance changes due to displacement

Thermal (bubble) effect - measures heat transfer changes

Optical methods - uses light interference patterns

Each technology has unique advantages and limitations. The most basic principle remains consistent: a medium deforms due to acceleration, and this deformation is converted into a measurable electrical signal.

II. Classification of Acceleration Sensors

1. Piezoelectric Accelerometers

Piezoelectric acceleration sensors, also called piezoelectric accelerometers, belong to the category of inertial sensors. They utilize the piezoelectric properties of materials such as piezoelectric ceramics or quartz crystals. When the sensor experiences vibration, the force applied to the piezoelectric element by the seismic mass changes accordingly.

Figure 3. Cross-section of a Piezoelectric Accelerometer

When the measured vibration frequency is significantly lower than the sensor's natural frequency, the force change is proportional to the measured acceleration. These sensors are particularly effective for dynamic measurements and high-frequency vibration analysis.

Advantages:

Wide frequency range (typically 1 Hz to 10 kHz or higher)

High sensitivity

Excellent linearity

Self-generating (no external power needed for basic operation)

Robust and reliable

Limitations:

Cannot measure true DC (static) acceleration

Requires charge amplifier or voltage amplifier

Temperature sensitivity

2. Piezoresistive Accelerometers

Piezoresistive acceleration sensors leverage advanced MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems) silicon micromachining technology. These sensors offer several key advantages:

Extremely small size (often less than 5mm)

Very low power consumption (microampere range)

Easy integration with analog and digital circuits

Can measure from DC (0 Hz) to several kHz

Cost-effective for mass production

These sensors are widely used in automotive crash testing, equipment vibration monitoring, structural health monitoring, and consumer electronics. The piezoresistive effect causes resistance changes in semiconductor materials when subjected to mechanical stress, which can be measured using a Wheatstone bridge configuration.

3. Capacitive Accelerometers

Capacitive acceleration sensors operate based on changes in capacitance. They typically consist of fixed plates and a movable proof mass. When acceleration occurs, the proof mass moves, changing the gap between capacitor plates and thus altering the capacitance.

These sensors have become dominant in many applications, particularly:

Automotive airbag systems

Smartphones and tablets

Wearable devices

Gaming controllers

Industrial equipment monitoring

Key advantages:

Excellent DC response (can measure static acceleration)

Low power consumption

High sensitivity

Good temperature stability

Cost-effective with MEMS technology

Can be manufactured in very small sizes

Modern capacitive MEMS accelerometers often include built-in signal conditioning, digital interfaces (I²C, SPI), and programmable features, making them highly versatile for various applications.

4. Servo Accelerometers

Servo acceleration sensors represent a closed-loop measurement system with excellent dynamic performance, large dynamic range, and superior linearity. These are precision instruments used in demanding applications.

Figure 4. Servo Type Accelerometer

The vibration system follows the "m-k" (mass-spring) model, similar to other accelerometers, but includes an electromagnetic coil on the proof mass. When acceleration is applied:

The proof mass begins to deviate from its equilibrium position

A displacement sensor detects this movement

A servo amplifier processes the signal and converts it to current

This current flows through an electromagnetic coil

The coil generates a restoring force in a permanent magnetic field

This force attempts to maintain the mass at its original equilibrium position

Because of this feedback mechanism, servo accelerometers offer:

Enhanced anti-interference capability

Improved measurement accuracy (often better than 0.01% of full scale)

Extended measurement range

Excellent frequency response

These sensors are widely used in:

Inertial navigation systems

Inertial guidance systems

High-precision vibration measurement

Calibration standards

Aerospace applications

Seismic monitoring

III. Technical Parameters

1. Output Mode

The output type is a critical consideration that depends on your system's interface requirements. Modern acceleration sensors offer various output options:

Analog Output:

Voltage output: Typically proportional to acceleration (e.g., 2.5V = 0g, 2.6V = 0.5g)

Current output: 4-20mA signals for industrial applications

Charge output: From piezoelectric sensors, requires charge amplifier

Digital Output:

PWM (Pulse Width Modulation): Duty cycle proportional to acceleration

I²C: Popular two-wire serial interface

SPI: High-speed serial peripheral interface

UART: Universal asynchronous serial communication

CAN bus: For automotive and industrial applications

Figure 5. Pulse Width Modulation (PWM)

For microcontrollers with only digital inputs (like some basic development boards), digital output sensors are necessary. However, they require additional processing overhead to decode the signal.

For microcontrollers with analog-to-digital converters (ADC), such as modern ARM, PIC, AVR, or ESP32 platforms, analog sensors can be simpler to implement. A simple ADC read command can acquire the acceleration value in microseconds.

2025 Update: Most modern sensors now include digital interfaces with built-in ADC, signal processing, and even AI-capable features for edge computing applications.

2. Number of Measuring Axes

Acceleration sensors are available in different axis configurations:

Single-axis: Measures acceleration along one direction

Dual-axis (2D): Measures in two perpendicular directions (X and Y)

Triple-axis (3D): Measures in all three spatial dimensions (X, Y, and Z)

For most applications, a three-axis accelerometer is now the standard choice due to:

Complete motion detection capability

Ability to measure tilt in any orientation

Minimal cost difference compared to 2-axis versions

Single package simplicity

Three-axis sensors are essential for:

Drones and UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles)

Robotics and ROVs (Remotely Operated Vehicles)

Smartphones and tablets

Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) devices

Wearable fitness trackers

Advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS)

3. Maximum Measured Value (Measurement Range)

The measurement range, typically expressed in "g" (where 1g = 9.81 m/s²), should be selected based on your application:

±1.5g to ±2g: Suitable for tilt sensing, orientation detection, and low-impact applications

±4g to ±8g: General-purpose motion detection, gaming, and consumer electronics

±16g to ±50g: High-impact applications, sports analytics, crash detection

±100g to ±500g: Automotive crash testing, military applications

±1000g and above: Ballistics, explosive testing, extreme impact events

Consider these guidelines:

For measuring robot inclination relative to ground: ±2g is sufficient

For dynamic robot performance: ±4g to ±8g recommended

For sudden starts/stops or impact detection: ±16g or higher

For vehicle airbag systems: ±50g to ±100g typical

Important: Higher range sensors generally have lower resolution. Choose the smallest range that accommodates your maximum expected acceleration for best resolution.

4. Sensitivity

Sensitivity indicates how much the output changes per unit of acceleration. It's typically expressed as:

mV/g for analog voltage output sensors

pC/g (picocoulombs per g) for charge output sensors

LSB/g (least significant bits per g) for digital sensors

Higher sensitivity generally provides:

Better resolution for small acceleration changes

Improved signal-to-noise ratio (SNR)

More accurate measurements at low acceleration levels

However, sensitivity must be balanced with measurement range. The relationship is typically inverse: higher sensitivity means lower maximum range.

Calculation considerations:

Maximum Output = Maximum Acceleration × Sensor Sensitivity

Ensure this value doesn't exceed your measurement system's input limits. For optimal performance, select sensitivity that provides good signal strength while maintaining adequate headroom for your maximum expected acceleration.

5. Bandwidth (Frequency Response)

Bandwidth refers to the range of frequencies the sensor can accurately measure. It's often confused with sample rate but represents different characteristics:

Bandwidth specifications:

DC to 50 Hz: Tilt sensing, orientation, slow motion

DC to 100-500 Hz: Human motion, gesture recognition, general robotics

DC to 1-5 kHz: Vibration analysis, machinery monitoring

1 Hz to 10 kHz+: High-frequency vibration, acoustic analysis

For different applications:

Tilt measurement: 50 Hz bandwidth sufficient

Gaming and motion control: 100-200 Hz adequate

Vibration monitoring: 500 Hz to several kHz required

Impact detection: 1 kHz or higher recommended

Structural health monitoring: Application-specific, often 1-5 kHz

2025 Update: Modern MEMS accelerometers commonly offer bandwidths up to 8 kHz with sample rates exceeding 32 kHz, enabling advanced vibration analysis and predictive maintenance applications.

6. Resistance/Impedance Considerations

Output impedance is crucial for proper interface with your measurement system:

For analog sensors:

Some microcontrollers require source impedance below 10kΩ for accurate ADC readings

High-impedance sensors (>32kΩ) may not work properly with certain MCUs

Buffer amplifiers can solve impedance matching issues

For piezoelectric sensors:

Very high output impedance (megohms to gigohms)

Require charge amplifiers or high-impedance voltage amplifiers

Cable capacitance affects sensitivity

Best practices:

Check your microcontroller's ADC input impedance requirements

Use appropriate signal conditioning if needed

Keep cable lengths short for high-impedance sensors

Consider sensors with built-in amplifiers for easier integration

Modern solution: Most current MEMS accelerometers include integrated signal conditioning with low-impedance outputs (typically<100Ω), eliminating impedance matching concerns.

7. Cumulative Error and Drift

When using accelerometers for position tracking through integration, several error sources accumulate:

Integration process:

Measure acceleration at time interval Δt

Integrate once to get velocity: v = v₀ + a×Δt

Integrate again to get position: s = s₀ + v×Δt

Error sources:

Bias error: Constant offset in acceleration reading

Noise: Random fluctuations in measurement

Temperature drift: Sensitivity changes with temperature

Quantization error: Limited resolution of ADC

Sampling rate limitations: Missing rapid changes

Error accumulation:

Velocity error grows linearly with time

Position error grows quadratically with time

After just 1 minute, position errors can exceed meters

Mitigation strategies:

Use complementary sensors (gyroscopes, magnetometers, GPS)

Implement Kalman filtering or sensor fusion algorithms

Periodic recalibration or zero-velocity updates

Higher sampling rates reduce integration error

Temperature compensation

2025 Update: Modern IMUs (Inertial Measurement Units) combine accelerometers with gyroscopes and often magnetometers, using advanced sensor fusion algorithms and AI-based calibration to significantly reduce drift. Some units now include on-chip machine learning for improved accuracy.

IV. Applications of Acceleration Sensors

1. Vehicle Safety Systems

Acceleration sensors play a critical role in automotive safety, with applications including:

Airbag deployment systems:

Detect sudden deceleration during collision

Typical response time:<2 milliseconds

Multiple sensors determine crash severity and direction

Modern vehicles use 10-20 accelerometers

Anti-lock Braking Systems (ABS):

Monitor wheel deceleration

Prevent wheel lockup during braking

Improve vehicle control and reduce stopping distance

Electronic Stability Control (ESC):

Detect lateral acceleration during turns

Prevent skidding and rollover

Automatically apply individual brakes to maintain control

Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS):

Adaptive cruise control

Lane departure warning

Collision avoidance systems

Automatic emergency braking

Figure 6. Acceleration Sensors in Modern Automobiles

2025 Update: Autonomous vehicles now use arrays of high-precision accelerometers combined with IMUs for precise motion control, requiring accuracy better than 0.1% and update rates exceeding 1 kHz.

2. Game Control and Motion Sensing

Acceleration sensors revolutionized gaming by enabling intuitive motion-based controls:

Console gaming: Controllers detect tilting, rotation, and gestures

Mobile gaming: Smartphone accelerometers enable steering and aiming

VR/AR gaming: Head tracking and motion capture for immersive experiences

Fitness gaming: Activity tracking and movement recognition

By detecting changes in tilt angle, players can control game objects by tilting handheld devices forward, backward, or side-to-side, creating more engaging and interactive gaming experiences.

3. Automatic Screen Rotation

One of the most common applications in consumer electronics, acceleration sensors enable:

Automatic portrait/landscape orientation switching

Detection of device rotation and direction

Seamless user experience across different viewing angles

Power-efficient implementation (low-power mode for continuous monitoring)

The sensor detects the device's orientation relative to gravity and triggers the display to rotate the image to match the correct viewing orientation.

4. Electronic Compass Tilt Correction

Magnetic sensors (magnetometers) determine direction by measuring magnetic flux. However, when tilted, the measured geomagnetic flux changes, causing directional errors.

Figure 7. Electronic Compass with Acceleration Sensor Module

Acceleration sensors solve this problem by:

Measuring the tilt angle in real-time

Providing compensation data to the magnetometer

Enabling accurate compass readings regardless of device orientation

Supporting 3D compass functionality

This combination creates a tilt-compensated electronic compass that works accurately even when not held perfectly horizontal, essential for navigation applications.

5. GPS Navigation System Enhancement

GPS systems determine position by receiving signals from satellites. However, GPS has limitations in certain environments:

GPS dead zones:

Tunnels and underground passages

Urban canyons (between tall buildings)

Dense forests

Indoor environments

Parking garages

Acceleration sensors provide dead reckoning capability:

Continue tracking movement when GPS signal is lost

Integrate acceleration to estimate velocity changes

Combine with gyroscopes for direction information

Provide seamless navigation through dead zones

This integration of GPS and inertial navigation creates more reliable positioning systems, particularly important for:

Automotive navigation

Delivery and logistics tracking

Emergency services

Autonomous vehicles

6. Fitness Tracking and Pedometer Function

Acceleration sensors detect the AC (alternating) signal and vibration patterns created by human movement:

Step counting:

Detect regular vibration patterns during walking/running

Identify zero-crossing points in acceleration waveform

Count steps with high accuracy (typically >95%)

Distinguish between walking, running, and other activities

Figure 8. Pedometer with Built-in 3D Acceleration Sensor

Advanced fitness metrics:

Distance calculation using step length and count

Calorie expenditure estimation

Activity type recognition (walking, running, cycling, swimming)

Sleep quality monitoring

Fall detection for elderly care

2025 Update: Modern fitness trackers use machine learning algorithms with accelerometer data to provide highly accurate activity classification, energy expenditure calculations, and even detect specific exercises like push-ups, squats, or weightlifting movements.

7. Image Stabilization

Acceleration sensors enable both optical and digital image stabilization:

Camera shake detection:

Measure vibration and shake amplitude in real-time

Detect hand tremor frequencies (typically 1-12 Hz)

Provide feedback to stabilization systems

Stabilization methods:

Optical Image Stabilization (OIS): Physically move lens elements or sensor

Electronic Image Stabilization (EIS): Crop and shift digital image

Hybrid systems: Combine both methods for superior results

When excessive vibration is detected, the system can:

Lock the camera shutter until motion stabilizes

Adjust lens position to compensate for movement

Apply digital correction to captured images

Increase shutter speed to freeze motion

This ensures clear, sharp images even when shooting handheld or in challenging conditions.

8. Gesture Recognition

Modern gesture recognition systems use acceleration sensors to detect and interpret user movements:

Applications include:

Shake to activate: Wake device or trigger functions

Tap detection: Double-tap to activate screen or features

Rotation gestures: Flip to mute or switch modes

Gesture commands: Draw patterns in air for control

Wrist gestures: Control smartwatches without touching screen

The acceleration sensor detects motion patterns and, using signal processing or machine learning algorithms, interprets them as specific commands. This enables intuitive, hands-free interaction with devices.

2025 Update: AI-powered gesture recognition now enables complex motion patterns, sign language interpretation, and personalized gesture customization using on-device machine learning.

9. Hard Disk Protection

Although less common with the rise of solid-state drives (SSDs), acceleration sensors still protect traditional hard disk drives (HDDs):

Free-fall detection:

Detect when device enters free-fall state (all axes read ~0g)

Typical detection time: 5-20 milliseconds

Trigger protective measures before impact

Protection mechanisms:

Park read/write heads in safe zone

Stop disk rotation

Lock head assembly

Prevent data loss and physical damage

During normal operation, the magnetic head flies just nanometers above the spinning disk. Even slight vibrations can cause head crashes and data loss. The acceleration sensor provides early warning of potentially damaging events.

2025 Note: While HDDs are being replaced by SSDs in many applications, they remain common in data centers and high-capacity storage systems where this protection is still valuable.

10. Device Orientation and Pose Detection

Acceleration sensors, often combined with gyroscopes and magnetometers in an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), enable comprehensive pose detection:

Figure 9. Motion-Sensing Applications

Sensor fusion benefits:

Accelerometer: Measures tilt using gravity, affected by motion

Gyroscope: Measures rotation rate, drifts over time

Magnetometer: Measures heading, affected by magnetic interference

Combined: Each sensor compensates for others' weaknesses

Applications:

Virtual reality headset tracking

Drone flight stabilization

Robot navigation and balance

Augmented reality positioning

Motion capture for animation

Sports performance analysis

Modern sensor fusion algorithms (Kalman filters, complementary filters, or AI-based methods) combine data from multiple sensors to provide accurate, drift-free orientation information.

11. Smart Wearables and IoT Applications

Acceleration sensors are fundamental to the rapidly growing wearable and IoT markets:

Smartwatches and fitness bands:

Activity tracking and classification

Heart rate measurement assistance

Sleep stage detection

Gesture control

Fall detection and emergency alerts

Healthcare applications:

Parkinson's disease tremor monitoring

Gait analysis for rehabilitation

Seizure detection

Elderly fall prevention

Post-surgery recovery tracking

Industrial IoT:

Predictive maintenance through vibration analysis

Equipment health monitoring

Structural integrity assessment

Transportation and logistics tracking

Asset management

Smart home applications:

Door/window open detection

Appliance usage monitoring

Security systems

Energy management

Figure 10. Three-Axis Acceleration Measurement in Smart Devices

2025 Update: The integration of AI at the edge has transformed accelerometer applications. Modern sensors include on-chip neural networks that can classify activities, detect anomalies, and make decisions locally without cloud connectivity, enabling:

Real-time health monitoring with medical-grade accuracy

Predictive maintenance with failure prediction weeks in advance

Personalized fitness coaching with form correction

Enhanced privacy through local processing

Reduced power consumption and latency

V. Installation Considerations

Proper installation is crucial for accurate acceleration measurements. The mounting method significantly affects the sensor's frequency response and measurement accuracy.

Key considerations:

Sensor weight relative to test structure

Frequency range of interest

Expected acceleration amplitude

Temperature range during testing

Environmental conditions (vibration, shock, humidity)

Mounting surface characteristics

Mounting Methods and Adhesives

The choice of adhesive directly impacts the sensor's natural frequency and coupling efficiency:

1. Stud mounting (permanent):

Best frequency response (up to sensor's full bandwidth)

Most rigid coupling

Requires threaded hole in test surface

Ideal for: High-frequency measurements, permanent installations

2. Adhesive mounting:

Cyanoacrylate (super glue):

Excellent frequency response (typically >10 kHz)

Fast curing (seconds to minutes)

Good for temporary installations

Temperature range: -50°C to +100°C

Removal: Acetone or heat

Figure 11. Cyanoacrylate Adhesives for Sensor Mounting

Epoxy adhesives:

Very strong, permanent bond

Excellent frequency response

Longer curing time (hours)

Temperature range: -50°C to +150°C

Difficult to remove

Hot glue:

Moderate frequency response (typically<5 kHz)

Easy application and removal

Good for temporary testing

Limited temperature range

3. Magnetic mounting:

Quick attachment/removal

Good frequency response on ferromagnetic surfaces

Limited to flat, smooth surfaces

Frequency response: typically up to 2-7 kHz

Ideal for: Quick surveys, multiple test points

4. Wax mounting:

Temporary mounting for light sensors

Easy removal with heat

Limited frequency response (<2 kHz)

Temperature sensitive

Good for: Quick tests, delicate surfaces

5. Double-sided tape:

Quick and clean installation

Moderate frequency response (<3 kHz)

Easy removal

Suitable for low-frequency measurements

Installation Best Practices

Surface preparation:

Clean mounting surface with hydrocarbon solvent (isopropyl alcohol, acetone)

Remove oil, grease, paint, or rust

Ensure surface is dry before applying adhesive

For best results, lightly sand or grind surface flat

Adhesive application:

Use minimal amount of adhesive

Apply thin, uniform layer

Avoid thick adhesive layers (reduces frequency response)

Ensure no air bubbles trapped

Apply firm pressure during curing

Important guidelines:

Sensor weight should be<10% of test structure mass (ideally <1%)

Mount sensor close to point of interest

Ensure mounting surface is rigid (not flexible)

Align sensor axes with desired measurement directions

Protect cables from vibration (strain relief)

Avoid mounting near heat sources if possible

Allow adequate curing time before testing

Temperature considerations:

Don't apply adhesive near maximum temperature limits

Allow adhesive to cure at room temperature when possible

High temperatures reduce adhesive strength

Consider thermal expansion differences

Use high-temperature adhesives for hot environments

Verification:

Tap test to verify good coupling

Check for resonances in frequency response

Compare with reference measurements if possible

Monitor for changes over time

2025 Update: Modern MEMS accelerometers often come in surface-mount packages designed for PCB integration, eliminating many traditional mounting concerns. For these devices, proper PCB design (rigid mounting, adequate ground planes, vibration isolation from other components) becomes the critical factor.

VI. Future Trends (2025 and Beyond)

The acceleration sensor industry continues to evolve rapidly with several emerging trends:

1. AI Integration and Edge Computing:

On-chip neural networks for real-time pattern recognition

Self-calibration and adaptive filtering

Predictive maintenance with AI-powered anomaly detection

Personalized health monitoring algorithms

Energy-efficient inference at the sensor level

2. Ultra-Low Power Operation:

Nano-watt power consumption in sleep modes

Energy harvesting integration

Always-on context awareness

Multi-year battery life for IoT devices

3. Enhanced Performance:

Noise levels below 10 µg/√Hz

Bias stability better than 1 mg over temperature

Wider bandwidth (DC to 10+ kHz in compact packages)

Higher shock survival (>10,000g)

Improved temperature stability

4. Miniaturization:

Package sizes below 1mm × 1mm

Integration with other sensors in single package

Flexible and stretchable sensor arrays

Implantable medical-grade sensors

5. Advanced Applications:

Autonomous vehicles: Sensor fusion for precise motion control

Healthcare: Continuous health monitoring and early disease detection

Industry 4.0: Predictive maintenance and digital twins

Smart cities: Infrastructure health monitoring

Space exploration: Navigation and scientific measurements

Quantum sensing: Ultra-precise measurements for research

6. Connectivity and Standards:

Wireless sensor networks with mesh capability

5G and IoT protocol integration

Standardized interfaces (IO-Link, OPC UA)

Cloud connectivity with edge processing

Blockchain for sensor data integrity

7. Environmental Considerations:

Lead-free and RoHS compliant manufacturing

Recyclable materials and sustainable production

Reduced environmental impact

Longer product lifecycles

8. Security:

Hardware-based encryption

Secure boot and firmware updates

Authentication mechanisms

Protection against tampering and spoofing

📚 Recommended Articles:

What are Weight Sensors? 50 World Famous Sensor Manufacturing Companies Types and Application of Position Sensors What is an Oxygen Sensor?

📝 Article Update Information:

Original Publication: 2020

Last Updated: November 2025

Major Updates:

Added section on AI integration and edge computing capabilities

Updated technical specifications to reflect 2025 state-of-the-art

Expanded applications section with modern use cases

Added future trends section covering emerging technologies

Corrected terminology (e.g., "cache mechanism" to "impedance considerations")

Updated information on autonomous vehicles and IoT applications

Enhanced mobile-responsive formatting with improved styling

Added context about SSD replacing HDD in many applications

Updated sensor fusion and machine learning applications

Next Review: Scheduled for Q4 2026

This article provides general information about acceleration sensors. For specific applications, always consult manufacturer datasheets and application notes.

1.How does acceleration sensor work?

An accelerometer is a device that measures the vibration, or acceleration of motion of a structure. The force caused by vibration or a change in motion (acceleration) causes the mass to "squeeze" the piezoelectric material which produces an electrical charge that is proportional to the force exerted upon it.

2.Where are accelerometers used?

Accelerometers can be used to measure vibration on cars, machines, buildings, process control systems, and safety installations. They can also be used to measure seismic activity, inclination, machine vibration, dynamic distance, and speed with or without the influence of gravity.

3.What is the function of accelerometer sensor in mobile phones?

Accelerometers in mobile phones are used to detect the orientation of the phone. The gyroscope, or gyro for short, adds an additional dimension to the information supplied by the accelerometer by tracking rotation or twist.

4.What is the working principle of accelerometer?

The basic underlying working principle of an accelerometer is such as a dumped mass on a spring. When acceleration is experienced by this device, the mass gets displaced till the spring can easily move the mass, with the same rate equal to the acceleration it sensed.

5.What is the difference between speed and acceleration?

Speed is the rate of change of distance(basically how much distance(m) has been covered in a particular time(s)). Velocity is the rate of change of displacement( change of distance in a particular direction with respect to time), and acceleration is the rate of change of velocity per unit of time.

The Key Role of Electronic Components in IoT DevicesUTMEL01 September 20234978

The Key Role of Electronic Components in IoT DevicesUTMEL01 September 20234978The article discusses the pivotal role of electronic components in Internet of Things (IoT) devices. IoT devices work by capturing real-world data using sensors, processing it through a microcontroller, and then sending it to the cloud for further analysis.

Read More How to Identify the Perfect Proximity Sensor for Your ApplicationUTMEL19 July 2025886

How to Identify the Perfect Proximity Sensor for Your ApplicationUTMEL19 July 2025886Find the best proximity sensors for your project by evaluating material, sensing range, environment, and system needs to ensure optimal performance and reliability.

Read More Trusted Vibration Sensors for Homeowners and Industry ProfessionalsUTMEL17 July 2025597

Trusted Vibration Sensors for Homeowners and Industry ProfessionalsUTMEL17 July 2025597Compare top vibration sensors for home and industrial use. Find trusted options for security, predictive maintenance, and equipment protection.

Read More Wiring and Mounting Photoelectric Sensors in 2025UTMEL15 July 2025794

Wiring and Mounting Photoelectric Sensors in 2025UTMEL15 July 2025794Wire and mount photoelectric sensors in 2025 with step-by-step safety, wiring, and alignment tips for reliable installation and optimal sensor performance.

Read More Essential Tips for Picking the Best Gas SensorUTMEL15 July 20251877

Essential Tips for Picking the Best Gas SensorUTMEL15 July 20251877Find out how to select gas sensors by matching target gases, environment, and compliance needs for reliable and accurate gas detection in any setting.

Read More

Subscribe to Utmel !